Digital Silk Road: AI Exports Reshaping Global Tech Power

In the rapidly evolving landscape of global technology and geopolitics, China’s Digital Silk Road (DSR) has emerged as a pivotal extension of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2015.

This initiative, initially focused on physical infrastructure, has shifted toward digital connectivity, with artificial intelligence (AI) at its core. By 2025, the DSR’s role in exporting AI technologies has become a critical lens for understanding China’s ambition to challenge the technological dominance of the U.S. and the EU while fostering economic and political ties with developing nations.

Understanding the Digital Silk Road: Origins and Evolution

The DSR was first introduced by President Xi Jinping in 2015 during a speech at the University of Ghana, envisioning enhanced digital connectivity along historical Silk Road routes. Over the years, it has evolved to encompass telecommunications networks, cloud computing, e-commerce platforms, surveillance systems, and AI technologies.

By 2024, it had become integral to China’s strategy to lead the Fourth Industrial Revolution, as outlined in its 2017 New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan, which sets a goal to become a global AI leader by 2030 and emphasizes international cooperation.

Chinese tech giants—Huawei, Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu—play central roles, leveraging state support to expand globally. This evolution is evident in recent developments, such as the third Belt and Road Forum in October 2023, where China announced a shift to “small yet smart” initiatives, focusing on digital infrastructure and governance.

AI Technologies: The Core of DSR Exports

AI is the heartbeat of the DSR, with China exporting a range of solutions tailored to developing markets. These include:

Facial Recognition Systems: Companies like Cloudwalk have deployed systems in Zimbabwe, collecting biometric data from millions, raising privacy concerns.

Smart City Solutions: Huawei has built AI-driven smart cities in Southeast Asia and Africa, integrating technologies for traffic management and public safety.

E-commerce Platforms: Alibaba’s investment in Lazada in July 2023 and TikTok’s acquisition of Tokopedia highlight China’s digital market expansion (more below, in Southeast Asia related case studies).

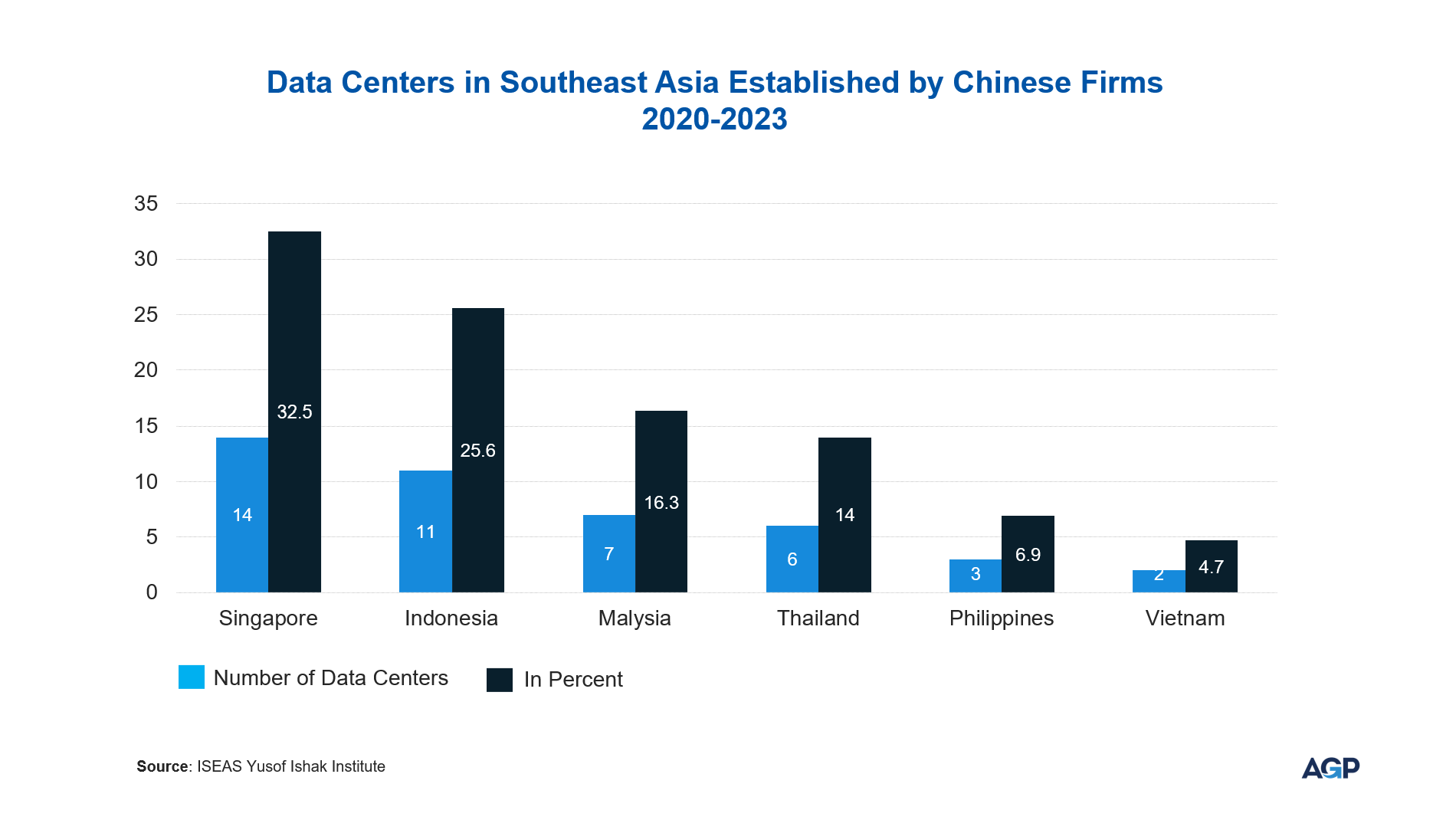

Data Centers: Between 2020 and 2023, Chinese firms established 43 data centers across Southeast Asia, a significant move that underscores the Digital Silk Road’s (DSR) ambition to expand China’s digital influence in the region.

This development, driven by companies such as Huawei Cloud, Alibaba Cloud, Tencent Cloud, ZTE, GDS, and DYXnet, reflects a strategic push to meet the growing demand for cloud computing, AI, and e-commerce infrastructure in Southeast Asia’s fast-evolving digital economy.

Case Studies and Recent Developments

To illustrate the DSR’s impact, consider the following case studies:

Thailand

In 2024, Thailand accelerated its adoption of Huawei’s 5G infrastructure, positioning itself as a regional leader in digital transformation and a testing ground for AI-driven smart city solutions, directly aligning with the Digital Silk Road’s (DSR) goals of expanding China’s technological influence.

A landmark achievement was the implementation of the first 5G fully connected factory in Southeast Asia at Midea’s Industrial Park in Chonburi, a collaboration between Midea, AIS, China Unicom, and Huawei, announced in May 2024. This factory leverages a dedicated 5G private network to enable real-time data collection, AI inspection, and automated guided vehicles (AGVs), achieving a 75% reduction in rework rates and a 4% increase in first-time yield.

Beyond manufacturing, Thailand’s smart city initiatives have gained momentum, particularly in Pattaya, where Huawei partnered with National Telecom (NT) to roll out the Pattaya Smart City project. Phase one, completed and operational by early 2024, integrates 5G, AI, and IoT through a network of 5G Smart Poles connected to an Intelligent Operation Center (IOC). This system enables real-time traffic management, weather monitoring, and emergency response, improving governance and quality of life for residents and tourists. Phase two expands to include enhanced AI, big data analytics, and interdepartmental data sharing, further embedding AI-driven solutions into urban management.

Thailand’s broader vision, announced in November 2023, aims to establish 105 smart cities by 2027, with Huawei’s 5G infrastructure as a cornerstone, supporting applications like digital signage and public safety systems on mmWave and 5G networks.

Malaysia

In late 2024, Malaysia signed a cybersecurity memorandum of understanding (MOU) with China, marking a significant step in deepening bilateral technological ties, with a specific focus on AI collaboration.

Announced in November 2024, this agreement builds on a history of telecom partnerships, notably Huawei’s ongoing 5G rollout in Malaysia, which began gaining traction in 2023. The MOU, signed during a high-level delegation visit to Beijing, aims to enhance Malaysia’s cybersecurity frameworks by integrating DSR technologies, such as AI-driven monitoring systems, into its national digital infrastructure. This collaboration aligns with Malaysia’s broader digital ambitions under the Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint, which seeks to position the country as a regional digital hub by 2030.

The agreement focuses on several key areas. First, it facilitates the adoption of AI technologies to strengthen cybersecurity, including the use of Huawei’s SecMaster technology and Cloud Bastion Host (CBH) solutions, which have been tested in prior collaborations, such as the 2024 MOU between Sarawak Information Systems Sdn Bhd (Sains) and Huawei Malaysia. These tools enable real-time threat detection and response, critical for safeguarding Malaysia’s growing digital economy, which contributed 23% to the nation’s GDP in 2023. Second, the MOU includes provisions for joint research and development in AI-driven monitoring systems, which can enhance public safety and governance but also raise concerns about surveillance. Third, it builds on Huawei’s 5G infrastructure in Malaysia, which by 2024 had expanded to cover 80% of populated areas, supporting applications like smart city initiatives in Kuala Lumpur and Penang.

However, the integration of DSR technologies, particularly AI-driven systems, has sparked debate. Critics, including local privacy advocates, warn of potential data sovereignty risks, citing China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law, which mandates data access for national security purposes. Proponents argue that the collaboration will bolster Malaysia’s cybersecurity capabilities, essential for protecting its digital economy amid rising cyber threats—Malaysia reported a 20% increase in cyberattacks in 2024, targeting financial and government sectors.

The MOU also positions Malaysia as a regional hub for China’s digital initiatives in Southeast Asia, potentially attracting further DSR investments but deepening technological interdependence. This development underscores the DSR’s role in exporting AI technologies, offering innovation opportunities for Malaysian enterprises while necessitating careful oversight to address security and ethical concerns.

Southeast Asia

Besides building digital infrastructure, Chinese companies have made significant investments in the region, cementing China’s role as a key player in Southeast Asia’s digital economy.

The effort reflects Beijing’s aim to integrate its technological ecosystem into fast-growing markets, enhancing connectivity and economic ties: Alibaba’s $845 million into Lazada (Singapore-based online retailer) in July 2023, Temu entering the Philippines in August 2023, and TikTok’s $1.5 billion acquisition of Tokopedia (Indonesia’s top online retailer) in early 2024.

The Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) reached $159 billion in 2024, up 15% from $138 billion in 2023 (Google-Temasek-Bain, 2024).

Africa

Since the DSR’s inception, Chinese tech giants like Huawei, ZTE, and China Telecom have embedded "Made in China" technology into Africa’s digital backbone. Between 2020 and 2024, these firms laid over 250,000 kilometers of fiber-optic cables, connecting more than 8 million households to broadband by early 2025, according to a Chinese Ministry of Commerce report. This infrastructure supports a surge in AI applications, exemplified by Cloudwalk’s facial recognition systems, now operational in at least five countries, including Zimbabwe and Uganda, where millions of biometric records have been collected since 2023. These systems, often marketed as public safety tools, have raised persistent privacy concerns, with critics citing weak regulatory frameworks across the continent.

A hallmark of the DSR’s expansion in Africa is the proliferation of smart city initiatives. By 2024, Huawei had partnered with over a dozen African governments to deploy AI-driven urban solutions, such as the Harare Smart City project in Zimbabwe and pilots in Ethiopia and Ghana. These projects integrate 5G, IoT, and real-time monitoring through networks of smart poles and CCTV cameras, achieving measurable gains—such as a 12% reduction in traffic congestion in pilot cities by early 2025.

Coupled with this, Chinese firms established 30 new data centers between 2021 and 2024, concentrated in hubs like Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa, powering cloud computing and e-commerce growth. Africa’s digital economy saw a 15% increase in Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) in 2024, reaching $90 billion, according to a 2024 Deloitte Africa report.

African nations have largely embraced Beijing’s offerings, supported by over $180 billion in loans and grants since 2005. A notable 2024 milestone was a continent-wide cybersecurity pact signed at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), enhancing AI-driven threat detection with tools like Huawei’s SecMaster, though it deepened technological interdependence.

However, this integration has sparked debate. Privacy advocates warn that unchecked data collection could enable governments to suppress dissent, a concern amplified by the absence of robust data protection laws in many countries. Conversely, proponents argue that DSR investments have slashed connectivity costs—data prices dropped from 8% to 5% of average monthly income between 2019 and 2024, per the Alliance for Affordable Internet—unlocking economic potential in a region where internet access remains a luxury for many.

Strategic Objectives

The DSR serves multiple strategic goals:

Technological Leadership: By exporting AI technologies through DSR initiative, China seeks to establish itself as a global leader in setting technological standards, a strategy that enhances its influence over international digital norms and challenges the dominance of the U.S. and EU.

This ambition is evident in China’s active engagement with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the UN agency responsible for digital technologies, where it has pushed for standards on AI and facial recognition that align with its state-driven model. At the ITU’s AI for Good Global Summit in May 2024, China advocated for standards on AI watermarking and digital content verification, emphasizing national security and state control over multi-stakeholder governance. This approach contrasts with models favored by other UN members, which prioritize input from civil society, industry, and academia alongside governments.

China’s influence extends to the UN General Assembly, where it has shaped AI governance narratives. In July 2024, the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted a China-proposed resolution on enhancing international cooperation in AI capacity-building, co-sponsored by over 140 countries. This resolution followed a U.S.-led AI resolution in March 2024, which promoted “safe, secure, and trustworthy” AI systems but favored broader collaboration. China’s version reflects its preference for centralized control, aligning with its domestic AI policies, such as the 2017 National Intelligence Law, which mandates data access for security purposes.

Economic Expansion: The DSR plays a pivotal role in driving economic expansion by opening new markets for Chinese firms, diversifying their revenue streams. This initiative enables Chinese tech giants like Huawei, Alibaba, and ZTE to penetrate emerging markets, particularly in Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, where demand for digital infrastructure is high. For instance, components of Huawei make up around 70% of 4G network in Africa[JC1] .

Similarly, Alibaba, Temu and TikTok investments previously mentioned have tapped into Southeast Asia’s $159 billion e-commerce market (2024 GMV).

Soft Power Projection: Through digital aid, China enhances its image as a reliable partner. This strategy leverages the DSR to build goodwill and influence in developing nations, positioning China as a collaborative ally. By providing technological assistance, training, and infrastructure, China addresses critical digital divides, fostering long-term economic and political ties while subtly promoting its governance model.

The U.S. has pushed for restrictions on Huawei’s 5G technology in Africa, citing security concerns, while the EU has emphasized regulatory frameworks like GDPR, which some African nations find restrictive.

Geopolitical Implications of the DSR

The DSR has far-reaching geopolitical implications that extend beyond its stated goals of technological leadership, economic expansion, and soft power projection.

By exporting AI and digital infrastructure to developing nations, the DSR has sparked significant controversy over digital sovereignty and data security, prompting governments in the U.S. and the EU to impose sanctions on Chinese firms like Huawei and ZTE. These sanctions reflect broader concerns about China’s growing influence over global digital ecosystems, the potential for surveillance, and the erosion of national autonomy in countries adopting DSR technologies.

The controversy over digital sovereignty centers on the ability of nations to control their digital environments, including data flows, infrastructure, and technological standards. The DSR’s expansion, particularly through projects like Huawei’s 5G networks and data centers, has raised alarms about the centralization of data in Chinese hands.

The DSR’s model, which often bundles technologies like AI, 5G, and smart city solutions, allows China to access large datasets, challenging the sovereignty of recipient countries by giving Beijing unprecedented control over their digital infrastructure.

Data security is another major concern driving geopolitical tensions. China’s domestic legal framework, including the 2017 National Intelligence Law, the Cybersecurity Law (CSL), Data Security Law (DSL), and Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), mandates that Chinese companies provide data to the government for national security purposes. These laws have extraterritorial reach, meaning that data collected by Chinese firms in DSR partner countries could be accessed by the Chinese state.

Final Thoughts

As the DSR enters its second decade, its significance as a geopolitical, technological, and economic force continues to grow. China’s integration of AI into its global digital infrastructure strategy offers both opportunities and challenges—enabling rapid digital transformation in developing markets while raising complex questions about data governance, sovereignty, and global norms.

For participating countries, the DSR provides access to affordable and scalable technologies that can accelerate national development and close digital divides. However, it also calls for careful consideration of long-term dependencies, data security frameworks, and the implications of aligning with any single technological ecosystem.

At the same time, the response from the U.S. and the EU underscores a broader shift in how digital infrastructure and AI are shaping international relations. Competing governance models and standards reflect differing values, but they also highlight the urgent need for more inclusive and transparent dialogue on global digital governance.

Ultimately, the trajectory of the DSR—and the global response to it—will shape not only who leads in the AI era but also how the world defines digital sovereignty and cooperation in an increasingly interconnected age.

Related Insights.